Traveling Presentation 17: “Separate” No More

“Tuskegee of the North”

Widespread segregation in the Jim Crow Era after the Civil War left few opportunities for African American youth to receive a university education or formal training in skilled trades. An African Methodist Episcopal minister, Walter Allen Simpson Rice, was determined to address the problem and in 1886 founded the Manual Training and Industrial School for Colored Youth in Bordentown, New Jersey.

Rice modeled his school on the Hampton and Tuskegee institutes, two of the pre-eminent all-black centers of learning of the time, and he consulted with renowned educator and Tuskegee founder Booker T. Washington on the design of Bordentown’s curriculum and philosophy.

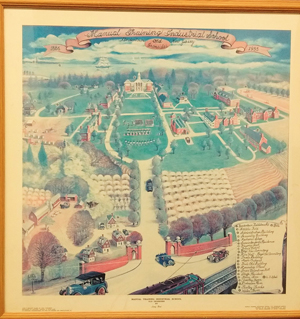

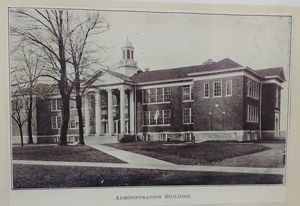

In 1897, Rice’s school, now state-governed and partially state-funded, moved from a couple of wood-frame row houses in Bordentown to a spacious tract of land overlooking the Delaware River. The land had once belonged to the commander of the famed battleship USS Constitution, “Old Ironsides,” as it was popularly known, and “Old Ironsides” would come to be used with affection to refer to the school itself.

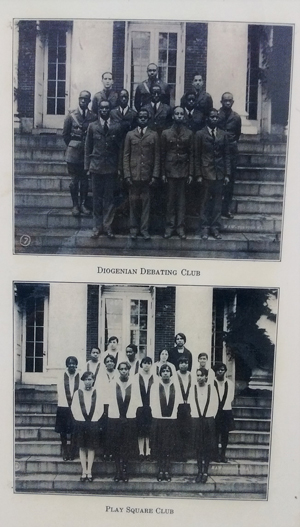

Bordentown accepted students at 14 years of age and graduated them with a high school diploma and a trade certificate. Tuition was free, with students responsible for paying monthly board, and students had to participate in the maintenance of the school by working on the school farm, performing janitorial services, firing boilers, waiting on tables, washing dishes, doing laundry and caring for the grounds. The farm was a significant source of income. Monies earned went toward the school’s upkeep and operations.

In its heyday in the first half of the 20th century Bordentown was renowned as the “Tuskegee of the North”. Its campus covered more than 400 acres and served as a social and cultural center for African Americans. Visitors included such notables as Booker T. Washington, Mary McLeod Bethune, Albert Einstein, Eleanor Roosevelt, Paul Robeson and W.E.B. DuBois.

But the school would not survive the dramatic changes that began to transform American society after World War II. With the rise of vocational education in public schools the state of New Jersey saw less need to support a separate, segregated institution. In 1947, when New Jersey required that all public and state-supported schools integrate, it became impossible for Bordentown to retain political and governmental support. In an effort to attract white students the word “Colored” was dropped from the school’s name, but the effort proved a failure. On June 30, 1955, one year after the U.S. Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka declared school segregation unconstitutional, “Old Ironsides” closed for good.

The property was taken over for several years by an institution for the developmentally disabled, which was fortunate because it allowed much of the original campus to survive. The 1990s saw renewed interest in Bordentown’s place in the history of black education as alumni and African American organizations joined forces to promote its significance. Twenty-two of its buildings have been entered in the New Jersey Registry of Historic Places. In 1998, the campus was placed on the National Register of Historic Places. Alumni have since purchased a quarter-acre of the property for the placement of a monument at the campus entrance to commemorate the legacy of the “Tuskegee of the North”.

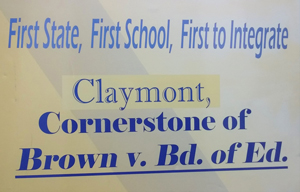

“First State, First School, First to Integrate

― Claymont, Cornerstone of Brown v. Bd. of Ed.”

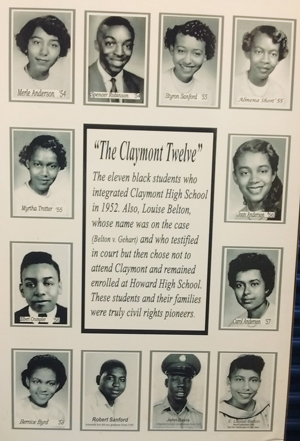

Three years before the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark

decision in Brown v. Board of Education overturned the legal basis for racial segregation in America’s public schools, a team of Civil Rights activists and lawyers led by prominent African American attorney Louis Redding sued the state of Delaware over its refusal to admit black students to its all-white schools. They won their case and in doing so helped establish a precedent for dismantling the constitutional doctrine of “separate but equal,” which the Supreme Court would do in 1954 in the Brown ruling. … As a result of the decision in Belton v. Gebhart, as the Delaware case is known, on September 3, 1952, the School Board of the city of Claymont voted to integrate. The next day, 12 African American teenagers attended their first day at Claymont High School. They were the first black students to legally enter a white public school in the 17 states where segregation was still the law at that time.

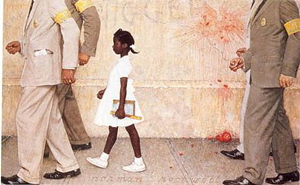

“The Problem We All Live With”

“The Problem We All Live With”

from a 1964 oil on canvas by Norman Rockwell

The popular artist and illustrator created a searing condemnation of racism with his iconic painting of Ruby Bridges on the day she became the first African American child to enter an all-white school in New Orleans. … It was 1960, six years after Brown v. Board of Education, and federal courts were ordering schools throughout the South to admit black students. Ruby’s father believed his daughter could get a perfectly good education in the city’s all-black schools, but her mother insisted that she pave the way for other African American children in the newly integrated New Orleans school system. On the morning of November 14, 1960, the 6-year-old did just that, entering William Frantz Elementary School with an escort of deputy U.S. marshals to protect her from hostile onlookers. … The power of the painting stems from its focus on the child, whose mother had instructed her that morning, “Now I want you to behave yourself today, Ruby, and don’t be afraid.” Thus, the men escorting her are faceless, as is the mob that has directed its hatred at her. Only the symbols of that hatred are visible: the racial slur, the letters “KKK,” the smashed tomato that was thrown at her. … There are hidden symbols in the painting, too, and students are encouraged to identify and discuss them.